Our Southside, Simon Square Site

Writing by Malcolm Fraser from a personal Essay first published in Alder, September 2022

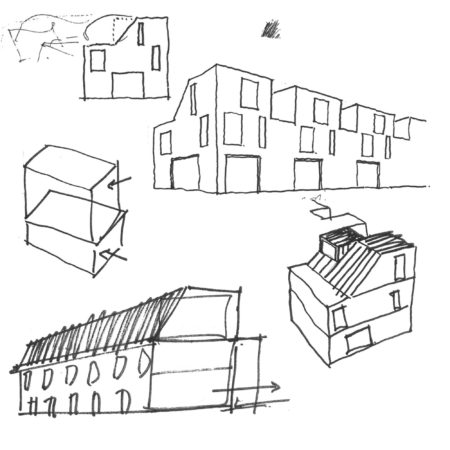

Ours is a tight little site, on a historic square in Edinburgh’s Southside and replacing a low-rise builder’s yard, surrounded by a diversity of 19th

century stone tenements and institutional buildings, and recent brick residential.

Achieving Planning Permission demanded a form that turned to avoid overlooking, but this requirement was further articulated to maximise views out and light in. The resultant chamfered edges and saw-toothed rooms not only provide good outlooks but define centred, flexible rooms. The tenemental form contains 6 flats, two per floor but with the upper extended up into a duplex with rooftop terrace. In this way the form pulls itself up to its north boundary, against its neighbour's blank gable, creating a small, shared entrance court to the south, protected from the street but enlivening it. The 4m tall boundary wall that overshadowed the neighbours has been lowered to 2.4m, letting light and space into their narrow rear courts. The modelled, chamfered and serrated timber-cored building form, at one and the same time, avoids overlooking neighbours' windows, directs views out to trees and along the street to good local buildings, grabs the sun and makes good, useful room shapes, most of which benefit from light from two or more sides.

Our timber structure is wrapped in a brick shell, with a lime slaister-coat dragged across it, to lose the "brickiness" and attain a satisfying, monolithic solidity. Our chamfered form with our big picture windows, and lime-slaistered masonry, sits contemporary in the street and Southside. Outside the cross-laminated-timber and inside the brick skin is woodfibre insulation and a ventilated cavity, all achieving our vapour-open construction.

CLIENT / Seven Hills Property

ARCHITECT / Fraser/Livingstone Architects

Gross Internal Area / 6 flats, 434m2

Brief / Private apartments to replace an existing workshop

Completion / June 2022

Urban Venaculars

Victorian Scotland developed a powerful urban vernacular that, propelled by a rhythm of bay-windows, marches up and down its slopes and addresses its public realm in a wonderfully muscular, cliff-like, plastic way – see the confluence of canyons at Boroughmuirhead, at the heart of my neighbourhood.

Developed out of a historic, palatial oriel window tradition, the bay windows were first deployed as part of an urban form in Edinburgh's New Town, in the 1790s oriels of the n-s-running North Castle Street, set to catch the sun from the south and, pre the tall trees of Queen Street Gardens, views out across the Firth of Forth to the north. Coupled with the fabulous craft skills of our stonemasons, the Victorians then evolved a tenemental form which extended Scotland's characteristic dense, social, highly-crafted mediaeval urbanity out from its historic city cores.

I'm getting the benefits of it now, sitting in my late-Victorian first floor bay writing this, bathed in light and happily-distracted by my neighbours' comings and goings, including a wee wave with my colleague Andrew, who walks up the main road and is sharper into the Studio of a morning.

The interlocking stonemasonry and sash-and-case windows of the bays, and the stone tenemental urban forms in general, were created by a fusion of fabulous craft skills, with all paid pittances and with the stonemasons who were craft royalty soon dead of silicosis; as well as by the major extraction of local stone from our quarries. The pittances, and the material extraction, are no longer a sustainable way of building, but while we have rediscovered the benefits of dense and social cityscapes the buildings we add to those urban environments are pale scenic facsimiles of their forbears, thrown-up and decorated to look a bit like them, in a heritage-fawn way: brick-clad over strange, complex structural agglomerations, including timber “kit”, with the timber engineered to minimum structural thinness. Such thinness is only made possible by using high-grade, slow-growing Baltic and Russian timber – with all the associated carbon miles, Brexit delays and post-Ukraine bans. In its thinness it is vulnerable to rot, so requires being dipped in toxic treatments and wrapped in polythene, to try to keep it from decay. The resultant “poly bag” internal environments rely on extensive ventilation to disperse vapour, CO2 and particulates, so unhealthy environments often ensue. And in a vain attempt to fend-off their unconvincing historicism Planners sometimes enforce stone, in place of the brick, to try and gain the authenticity of solid stone buildings. But stone deployed as scenic heritage wallpaper is thin, Remington-smooth blandstone – strangely non-contextual. Scenic “vernaculars” are a failure.

FLA TEAM / Ayla Riome, Andrew Gillespie, Coll Drury, Malcolm Fraser, Robin Livingstone

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER / Elliott&Co

COSTS, PD / David Adamson Group

ACOUSTICS / RMP

SERVICES / Harley Haddow

MAIN CONTRACTOR / Truebuild

Where now for Vernaculars?

The vernacular is not, as some would have it, a style, but the simple response to using the materials and technologies to hand, to address the outstanding issues of the day.

So if stone and craft-skills, and an urban tradition of social-density, produced an admirable Scottish vernacular, how should that vernacular evolve, with a new appreciation for the social-density bit, when the stone and craft-skills parts are gone? What are the materials and technologies to hand, now, and what are the urgencies which should lead us to turn to them? How should we build the vernacular, now?

Solid timber is the structural material of the future, locally-sourced as a carbon-locking, circular economy exemplar. First, solid, heavy timber avoids the unhealthinesses of timber kit: no polythene or rot treatments are required with this vapour-open, solid construction, and when it is exposed internally the D-Limonene the timber gives-out has been shown to produce calm environments, with occupants’ hearts beating slower, and stress reduced. And, secondly, and obviously, it locks-up carbon, in a big, solid way. Finally, we have a plentiful supply to hand, in Scotland, of the fast-growing softwood that thick timber can use, and an urgent need to reforest a sustainable economy from our land.

Innovation

There has been little innovation in heavy timber tenemental construction in Scotland. Part of the reason for this is Scotland’s admirably-high acoustic control requirements, demanding 56dB reduction in noise – much higher than England’s and one of the highest in Europe, and difficult to achieve where heavy timber conducts impact sound between properties. CLT social housing has been built, though it has addressed the acoustic issue by covering-up its timber with plasterboard – losing its aesthetic and healthy properties.

There has been a single, pioneering collective self-build clt tenement with exposed clt – architect John Kinsley’s magnificent Bath Street initiative. We have, here, proved the concept for the developer-led market, with greatly-improved acoustic characteristics. The R&D we have led has been challenging and successful, showing the building to achieve a 62dB reduction, a full 6dB above the already-substantial Scottish standard.

Pays des Arbres

The group Reforesting Scotland has long set out a vision of a forested, carbon-locking nation whose regenerated woodlands are a living, economic resource. Mark Cousins has followed this by writing of the nation as a future “Pays des Arbres”, with a successful, responsible arboricultural hinterland and economy, refocussing us on natural renewables. Thus far the biggest drawback of using clt in Scotland is that the material, while perfect for our fast-growing, low-grade timber, has had no Scottish manufacturer and comes from Europe, with on-costs, carbon miles and non-circular-economy drawbacks that undermine its carbon positives. Things are slowly changing and we are working with Scottish start-ups to deliver the follow-ups, as well as investigating local acoustic bracket manufacturers.

Further, we have assisted friends in opening the first Scottish manufacturer of hemp insulation, in the Borders and adjacent to the farms that will grow the hemp. We hope that, in doing all this, we are assisting with the evolution of a new, timber, Scottish urban vernacular, and a Pays des Arbres.

PHOTOGRAPHY

FURTHER INFORMATION

RIBA Journal: Sound and vision work together at Fraser/Livingstone’s Simon Square

Architects' Journal: Fraser/Livingstone completes solid structural timber ‘tenement’ in Edinburgh

Dezeen: Fraser/Livingstone adds angular tenement to historical Edinburgh site

PRINCIPAL AWARDS

Edinburgh Architectural Association, 2022

Residential Award

Wood Award

Building of the Year

Structural Timber Awards, 2022

Private Housing, Finalist

Saltire Awards, 2023

Saltire Housing Award

Saltire Medal 2023

Scottish Home Awards, 2023

Innovation in Design

Scottish Design Awards, 2023

Gold Award

Architect's Journal Architecture Awards, 2023

Housing Project up to £5milion, shortlisted

Dezeen Awards, 2023

Housing, Longlist

BE-ST Accelerate to Zero Awards, 2023

Gamechanger Award, Shortlisted

RIAS Awards, 2024

RIAS Award

Timber Award