I have a friend who is part-Architect, part Borders Shepherd, and he sends me snippets of bone-dry Borders humour from the sheep pens, such as, overheard at Henderland: Shepherd: I hear Jimmy Laidlaw’s mither died. Farmer 1: Whit, again? Farmer 2: Must be serious this time.

These structures – faulds in the lowlands, like a sheep fold, fanks in the Highlands (and bouchts in Orkney, crö in Shetland) – stud rural Scotland, some ruinous, some still in use, and when I see them I think on how their cold hillsides come alive as they are warmed-up by work: by lambing, dipping and shearing, and all the breath and blather of the humans and their livestock within.

They are work-stations, carefully laid-out to contain and control the enclosure, movement and treatment of the sheep, their design driven by the economy of effort to construct them, as well as later ideals of order and control. Thus you see older, circular structures, whose geometries are entirely utilitarian, conforming to the least amount of material, and therefore effort, needed to enclose the most amount of space, and as circles structurally muscular, cheating, instead of catching, the wind while sheltering sheep in their lee; and next to them, post the age of agricultural-improvement, squared versions, their right angles conforming to the Age of Enlightenment’s wish to demonstrate our strict, ordered, straight-lined control over nature.

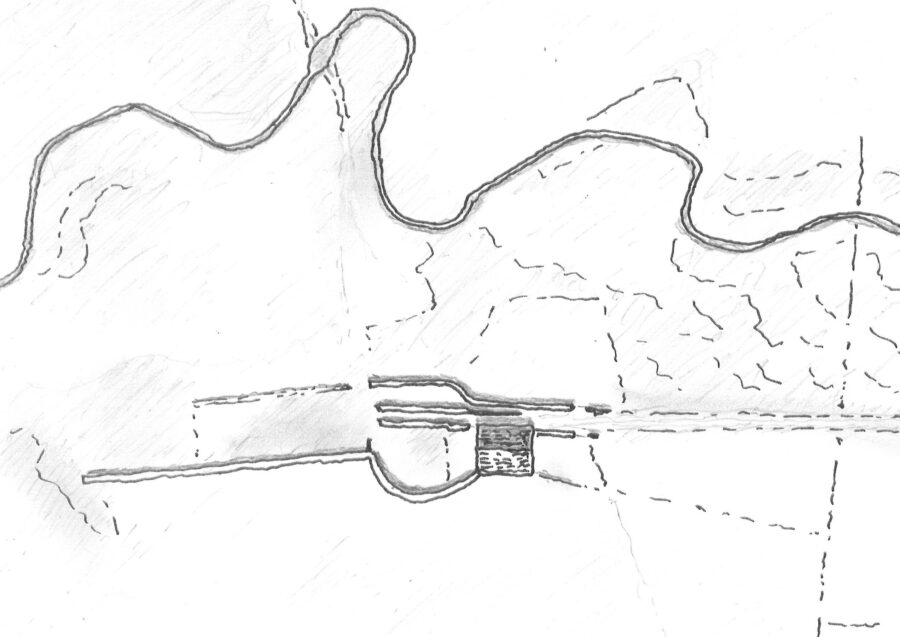

See: Whithope (fig. 1), above the Loch of the Lowes in the Borders, with its adjacent circular and improved arrangements, and also faulds below the Law in Nithsdale (fig. 2), with their complex flowering of circular folds fronting later, wider pens. But also see how sweet and economical the squared, improved geometries remain, with their sequences of gated buchts, when a perpendicular wall stops just short of a longer one, allowing sheep to be driven and controlled through the shedding gate, into the next pen.

And see the keb-hooses at Whithope and at Mountbenger Hope (fig. 3) in the Borders, where wee howffs sit at the heart of complex, contrasting geometries (fig. 4). A keb-hoose is a small shed or shelter where an ewe that has lost her lamb is confined while being groomed to adopt another, or more generally a shelter for young lambs in the lambing season and, no doubt, a warm haven and bothy for shepherds, their dogs, whisky and dry humour.

And, also, observe a characteristic inversion, that the more “primitive”, to the outside world, a community, the more sophisticated its vernacular sometimes becomes – must become, given the challenge of wringing a living from these austere places.

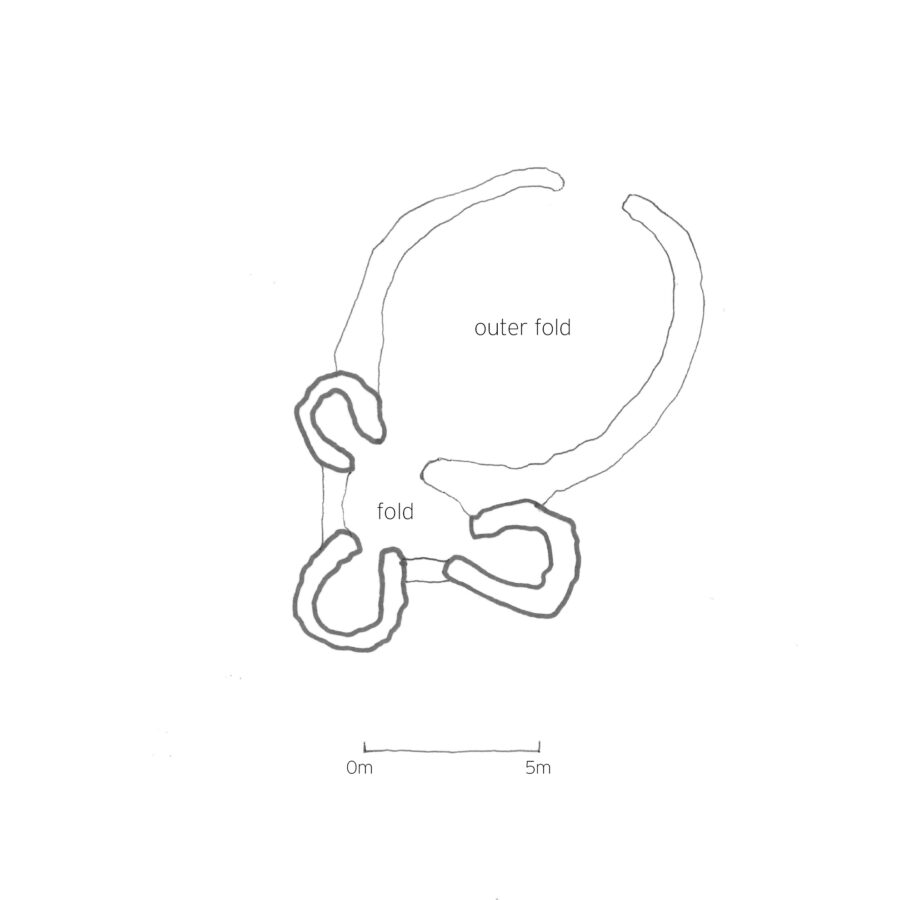

So there are fanks on St Kilda, that wild, wind-blasted violence of rocks way out in the Atlantic, whose population, resident since the Neolithic, was evacuated in 1930. They are in Gleann Mor, north of the main village. Looking at drawings of them (fig. 6), and before I knew of their function, I got unco excited, seeing some resemblance to hut groupings in Africa, like in the Nuba Mountains, where sleeping huts circle a shared, communal space, which gives out to some wider enclosure. So I dreamt of some new theory of historic St Kildan co-housing of ancient arrangement, older than the main village but over the other side of the hill, puzzlingly facing no beach or anchorage. Old island legend encouraged me, with one of the structures named by Victorian visitors as “The Amazon’s House”, reflecting local legends of a godlike woman who bestrode the sea.

But while the structures seemed to have incorporated some older – perhaps much older – buildings, on the ground they were too small, and were more recent. What I saw were faulds of fantastic intricacy (Fig. 5), formed by the unconscious, utilitarian cruelty of wringing a living from this most marginal of edges, with research suggesting they were devices to steal the richest milk from newly-birthed ewes, with their newborn lambs placed in the inner cells and their mothers herded from the outer into the inner fold where, frantic with the bleating from their confined wee ones, they gave-up their most nutritious, fatty milk to the islanders.

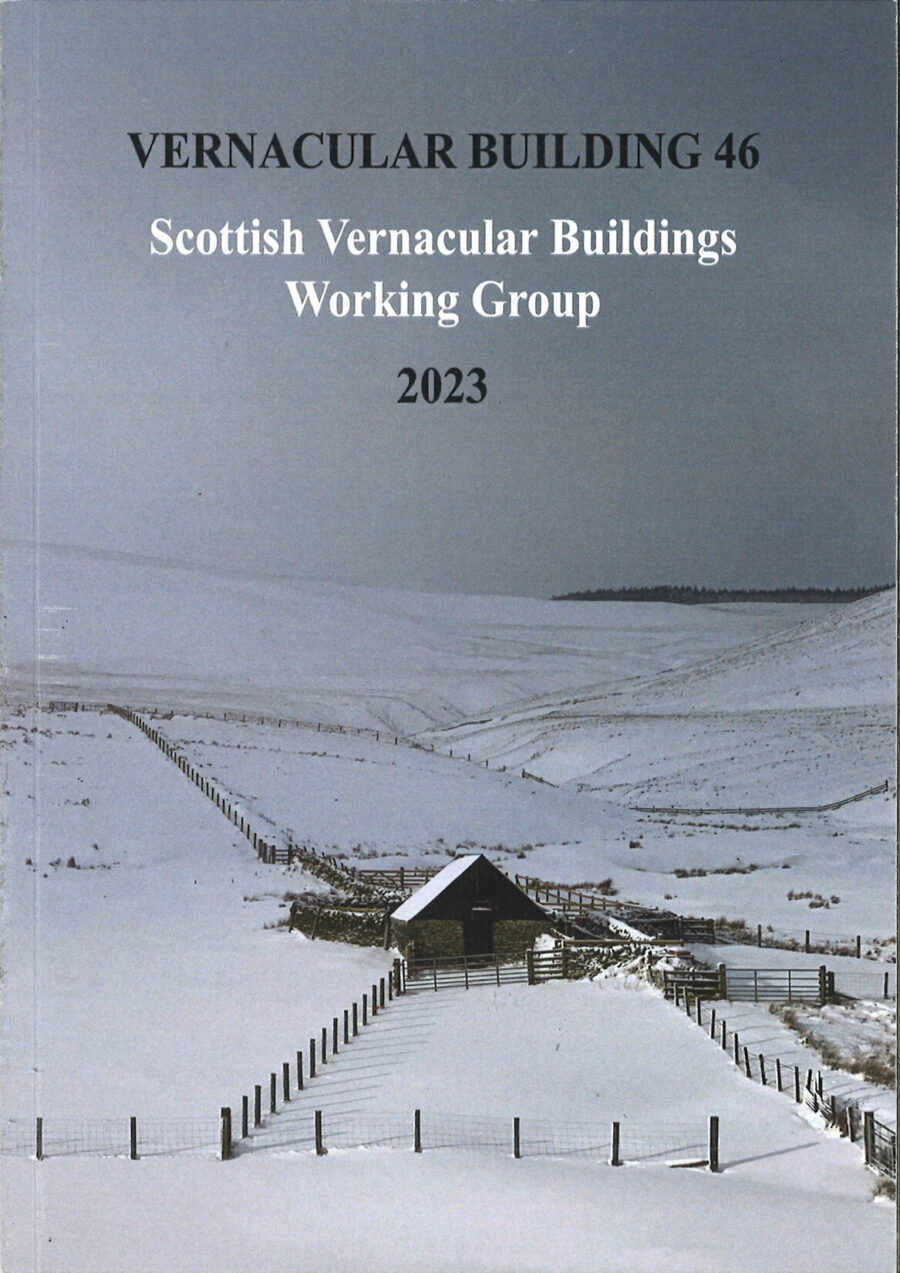

A Square Round

A Border Shepherd’s View, by Mikey Davidson, part-time Shepherd, part-time Architect

I have a friend, a redoubtable place-maker, from whom I receive word of the price of a pint of craft ale from the bars of our capital, via my satellite internet connection. On occasion, he’ll sail past the faulds at Henderland astride a pedal bike and can be heard pontificating upon the geometry of the utilitarian rural vernacular.

There is a distinction, perhaps usefully drawn, between faulds - where sheep are worked - and the more structurally sparse and geographically isolated sheepfolds, stells and enclosures which dot the landscape. Whilst stells might be augmented with a radial or extending dyke to enhance protection from the wind, or to aid gathering (the collection/relocation of sheep) from a certain direction, these structures did not originally provide for much, save the isolation and/or retention of a small number of sheep (for checking their health, trimming hooves, dressing wounds, and the likes) without the onerous process of gathering scattered (and very often obstinate) Blackface sheep and driving them all the way down to the farm. Traditionally, certain hefts (sheep which hold to a certain area of land through an innate sense of belonging) would have been attended to by a ‘herd on higher ground, sometimes fairly remotely from the main farm/steading. Such ‘herds and indeed their kin, might only repair to the lower lying farm and steading on seasonal sojourns. James Hogg, The Ettrick Shepherd, (1770-1835) in one instalment - Storms - of his Shepherd’s Calendar, remarks upon the remoteness of such outliers.

Such stells, though remote, would generally be located in an area of relative shelter and could provide sheep with a haven during the worst of the weather. Drystane circular stells are not only economic in terms of material but are built as such to provide structural rigidity against lateral wind loads. Perhaps counter-intuitively, sheep can also find shelter on the outside, forming a tapered flock making a teardrop shape on the leeward side of the stell, the geometric order and precision of which can appear carefully orchestrated and is fine-tuned by the wind’s direction. The circular shape also provides guaranteed shelter inside or out, regardless of wind direction. Constructed to the right size, snow will not settle inside. Too small, it is inefficient, too large and snow settles and drifts within. My grandfather referred to stells as 'rounds'. Above Henderland, at more than 1500ft, there is what is routinely referred to as the ‘square round’ – a small square enclosure, used as a stell. For reasons unknown to me, perhaps flamboyance, there is an octagonal stell at nearby Chapelhope.

Some rounds were later augmented by a small keb-house. Stone built, say 12 feet by 6, and internally compartmentalised by flakes (portable timber gates). These provided storage for winter feeding in locations cut off by bad weather, as well as the means to confine a yowe and new-born lamb together, often to aid the process of setting-on a lamb. The advantages of such infrastructure were extolled by another Ettrick shepherd (and cousin of Hogg) Alexander Laidlaw of Bowerhope. Laidlaw describes, in a letter to the Hon. Captain Napier of Thirlestane, which was published in the latter’s, “A treatise on Practical Store-Farming”, the layout of such houses and his implementation of them at the majority of the rounds on Bowerhope, followed by a rigorous comparison of the mortality of stock on his farm, relative to that of neighbouring Crosscleuch. He concludes with fervour (and no little eloquence) that such a plan “cannot fail to leave on the mind of every unprejudiced person, the strongest conviction of its utility”.

Faulds are more complex and comprise a series of interconnected buchts (pens) which will often be arranged in sequence of diminishing size. They will generally incorporate a shedding gate, through which sheep can be run, in order to shed off (separate) a specific group from another. Faulds will also often contain a race - a long narrow bucht - which can be used to bypass buchts, or indeed curtail the movement of sheep while dosing or jagging. Much work with sheep involves the separation, segregation and organisation of large numbers of sheep and a complex network of interconnected buchts can facilitate this. Control of gates subsequently becomes crucial and an unsnecked (unsecured) gate can undermine a fair amount of work.

These structures have come into being, incrementally. Their form arising over decades as they are periodically appended, modified and extended, adapting to provide a utilitarian platform for whatever tasks are to be performed there. Adaptations will arise for any number of reasons, and as the geographic centres of farms have altered. Mechanisation – particularly the introduction of ATVs and quad bikes - would have marked a significant shift and many outlying stells and faulds will have become redundant. That said, I suspect the faulds above Mountbenger Hope (fig. 7) have their origin in a simple stell and have been incrementally added to over the years.

As cycling place-makers are liable to contemplate, these faulds and stells would have traditionally been used to milk yowes (ewes). Note the lyrics of the traditional lament, Flowers of the Forest.

There are the remains of a large enclosure on the slopes of Craigie Rig, just above the Megget Dam, which was always referred to as the milkin' pens. I suppose, up until at least the early part of the 19th century for many folk, milk would have been associated with sheep primarily, rather than cows.

The sculptural, monolithic, geometry of stells, set so deliberately amongst the declivities of the landscape, makes these purposeful structures all the more captivating. Many are now ruinous monuments in a wild and beautiful, though far from natural setting. There is an agricultural vernacular, however, which perhaps has greater vitality. Farmers are pragmatists and this vernacular has a characteristic which is utterly unconcerned with aesthetics. Such structures are often held together around the edges by baling twine; augmented by a judiciously placed pallet or a ubiquitous wrinkly tin sheet. I can think of at least two recycled metal bedframes pressed into agricultural service upon completion of their domestic duties at Henderland. These improvised, sometimes erratic elements, are a sign that a fauld or enclosure is still in use. The authenticity of the vernacular, in this context, is not necessarily in the age or monolithic nature of drystane walls set in splendid isolation, but in its continued utility. Beyond being merely statuesque or stoic, they are, as Hogg might have it, furthersome.

Architecture is “nonstraightforward” of course and tension lies in this constantly unfolding vernacular language. Modern practices of any kind will tend to transcend and discard unwielding infrastructure. The maintenance of the many stells and the miles of drystone dyke which march across the landscape is now simply a question of economics. A dyke slowly lies down dead and eases itself into the ground at the foot of a post and wire fence, and there are fewer folk afoot the hills in the course of labour.

Lassies a-lilting before dawn o' day

- Photography: Malcolm Fraser unless stated

- Drawings: Malcolm Fraser, Felix Wilson