Andrew and Mirka explore how Orcadians have responded to the isles’ exposed and windswept conditions by creating an architecture centred around shelter.

PUBLICATION / RIAS Quarterly, Spring 2022

Landscape and early settlements

When asked to recall an Orkney upbringing, a parent’s windswept warning resounds - to open the car door with two hands. An image appears too, of causeways closed off by crashing waves, fresh washing in neighbours’ gardens,trampolines and henhouses relocated in the night, the lightest schoolkids with stones in their rucksacks to avoid take-off.

Wind was a constant. Without forests and Munros native to the Scottish mainland, and with the vast Atlantic to the West, unruly gusts sweep across the island with ease and with considerable force. These ceaseless gales have shaped our isles, our lives, and how we build.

The exposed, low-lying landscape and its flora is unique, and has been a lasting inspiration for writers, musicians, and painters. The poet Valerie Gillies, in collaboration with local photographer Rebecca Marr, produced a project based on wild grasses. In ‘Marram’, Gillies depicts our native beachside grass as a natural mechanism for shelter – a retaining wall of roots and woven strands:

its strong roots

sometimes twenty feet long creep through shifting sand

a glossy grass

protects the coastline engineer of the ecosystem

it creates vast areas

as the dunes become fixed and as other plants colonise marram gives way to them.

An understanding of the natural resilience of the isles translates from micro to macro. A visual artist who lovingly depicted the totality of her home in Orkney was Swedish- born photographer and ‘weel-kent’ local, Gunnie Moberg. Reflecting on her first visit to the isles in 1975, Gunnie wrote:

The wind wasn’t enough to dissuade, and a year later Moberg moved North with her family. A job at the local airport provided an opportunity to view the islands from above; she made pioneering photographs of what she saw, telling a story of isles moulded by a distinct Northern climate.

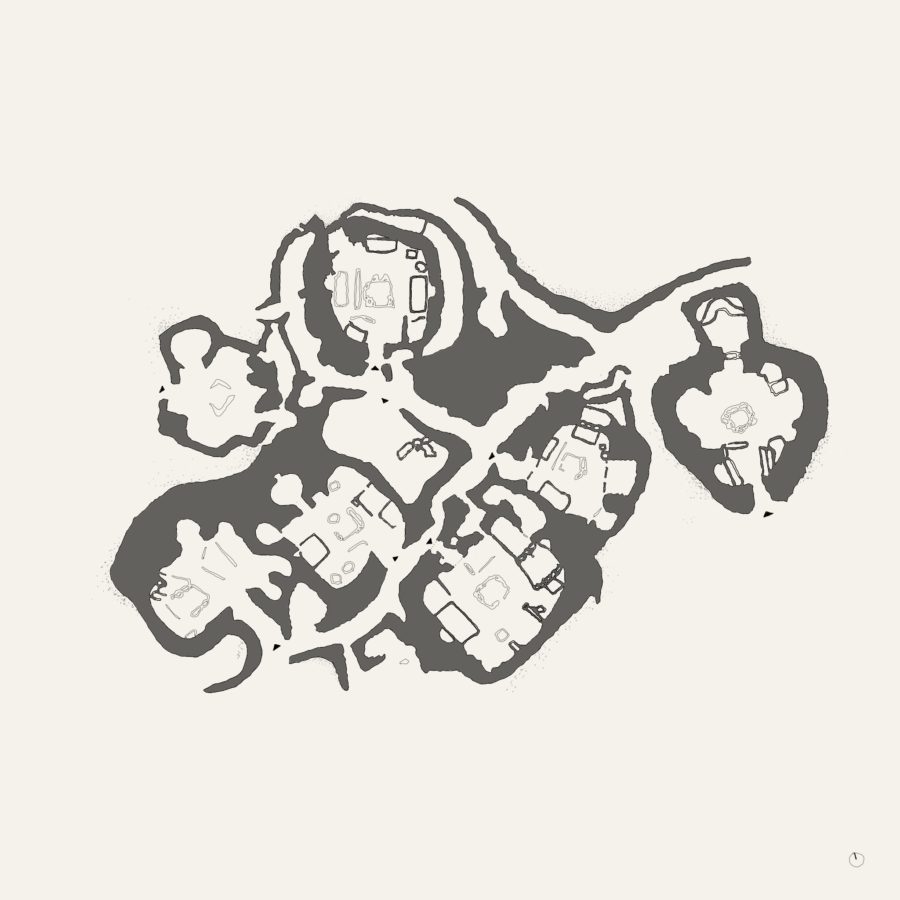

When primitive builders set out to establish a settlement at Skara Brae, conditions were equally challenging despite a vastly different climate. The temperature in 3000BCE Orkney was between three and five degrees warmer and their site, now famously on the edge of a deep bay on the West coast of the island, was once in-land. The settlement would’ve been protected somewhat by shrubs and low trees – some bearing fruit and nuts like apples and hazelnuts. When finding a site, settlers took advantage of what little opportunity there was for natural shelter; there are neolithic remains in a valley’s trough in the parish of Firth, submerged by the rising sea.

The settlement of Skara Brae was built from stone slabs split from raw bedrock. One-room, rounded homes responded to the low relief and grew organically beside one- another, connected by enclosed, narrow alleys. Dwellings were partially burrowed for cover, with a built-up midden banking for insulation and stiffening against the eternal wind. A hearth is centred in plan, around which spaces for cooking and sleeping were arranged.

Perhaps quaint now for their squat doors and stone furnishings, homes would’ve been very dark and smoky – without windows and possibly just a hole in a turf roof for ventilation. Life happened outdoors. The inhabitants are thought to be an agricultural people, their structures purely for shelter: a place to cook, sleep, and stay warm.

The early settlers responded to the isles with considered tread; established in Skara Brae and other Neolithic settlements around the island, was a close pattern of embedded dwellings reciprocal to the land.

Farms

A stone-built vernacular and a dependency on the land has endured. A farmer’s livelihood, whether prehistoric or modern, depends on the conditions of the land they farm.Orkney’s land is fertile and relatively flat, ideal for grazing and growing but consequently exposed to the elements. The response is an architecture distilled by necessity. Much of the land farmed across the island is used for improved pasture. A characteristic patchwork of grass and heather covers the island, marked with sheep and cattle stitched together with uncultivated strips of shrubs and shaggy grass, lochs, wire fences, or (more traditionally) drystone dykes. The latter breaks up the expansive green with a defined andcaptivating geometry, where ownership and undulations in the land are apparent, and shelter for livestock is created.

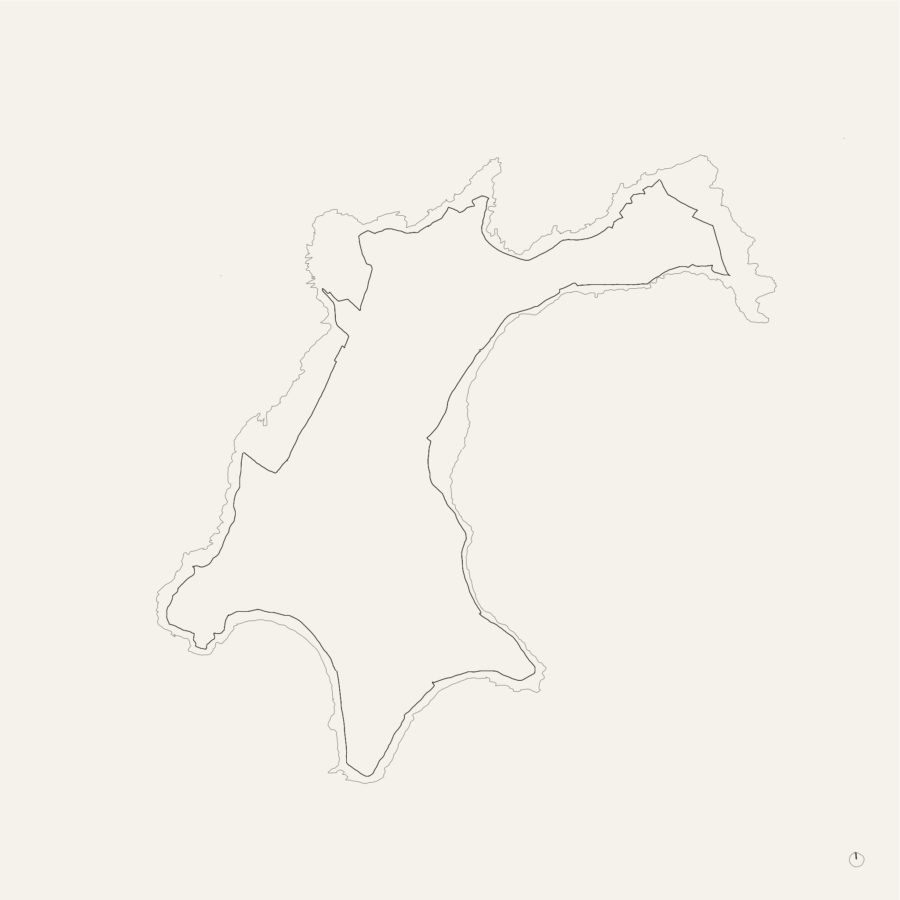

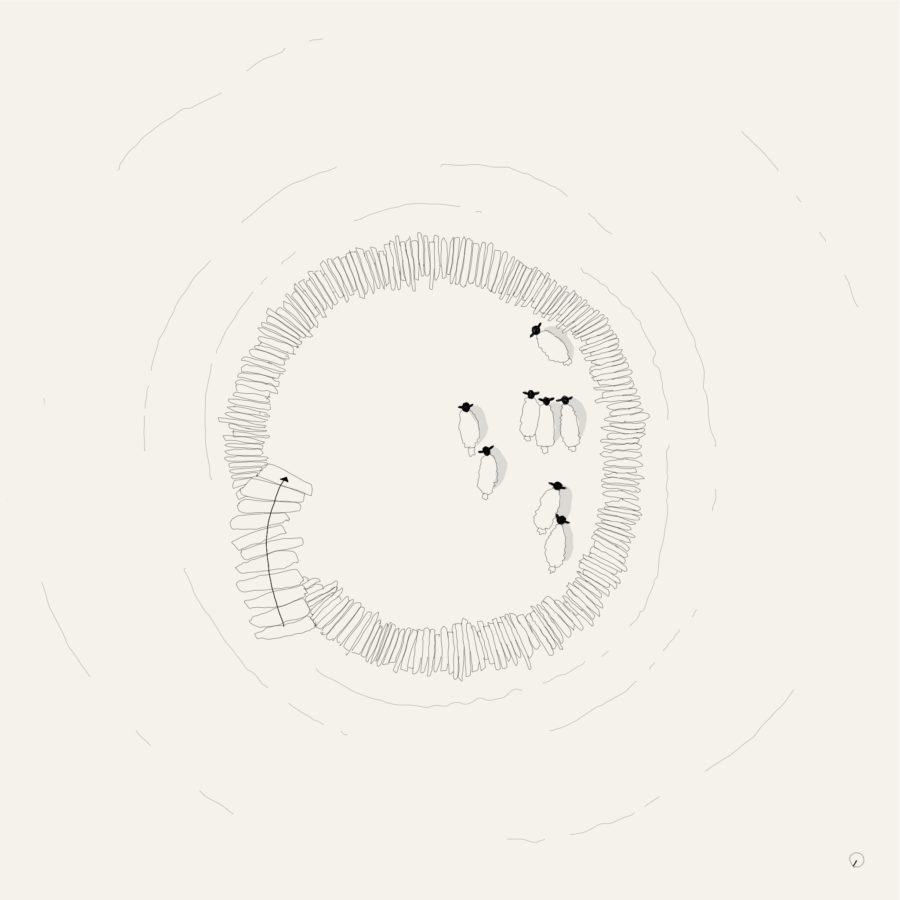

North Ronaldsay, Orkney’s outermost isle, is renowned for its impressive perimeter of stone; twelve miles of drystone construction encircles the island. Traditionally, walls are used to keep livestock in, but for North Ronaldsay’s sheepdyke the opposite is true. The profitable land for pasture and cattle is enclosed by the wall, keeping the sheep at the island’s coast to graze uniquely on kelp.

On overly exposed land, tailored solutions for shelter were devised. This simple answer was captured by Gunnie Moberg in her aerial photojournalism; a drystone cross marks the landscape, angular in form and elementary in construction. In any heart of wind, livestock are protected at the leeward junction. From above, a rugged land with a sentimental kiss of stone.

When faced with a land that disappears with the tide, a Westray farmer made use of a sheep’s ability to climb. A fort was built at low tide, accessible by a steep staircase up its side. As the tide rises, the sheep retreat up their tower to wait for water to recede and fodder to reappear.

Our long views are punctuated with these enduring stone structures, as at home in the landscape as our ancient settlements, stone circles, and chambered cairns.

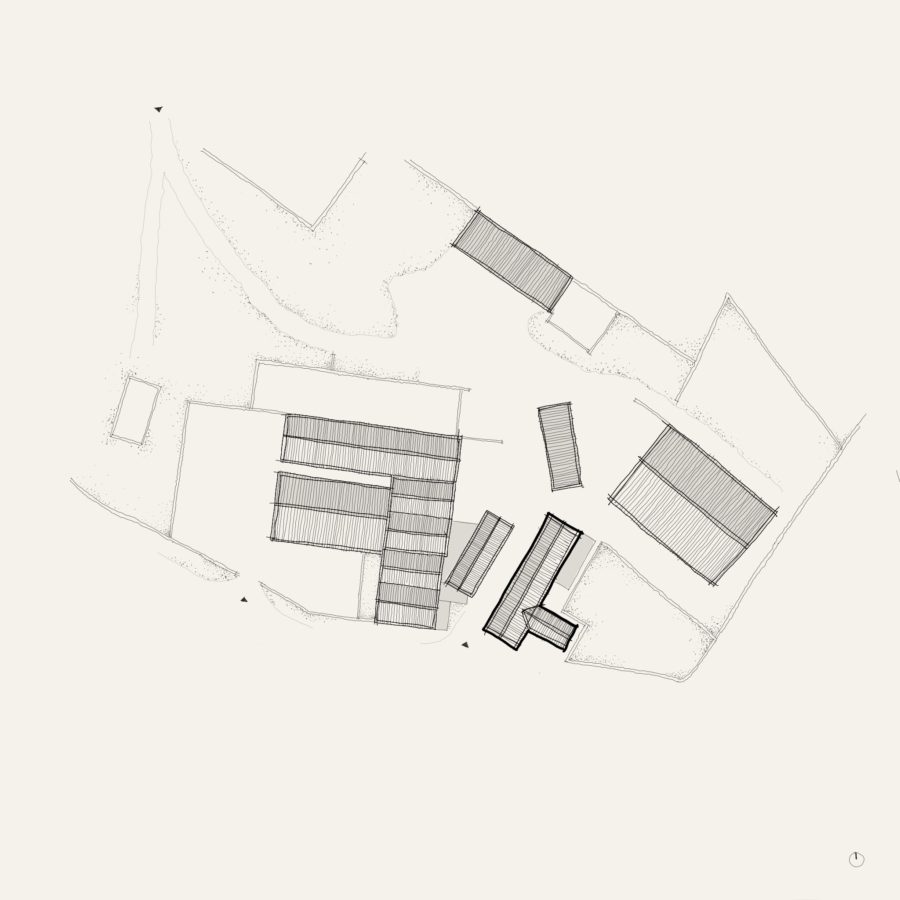

When making a mark on the landscape is objective, building on top of a hill is one way to do it. Located on the West shore of the Orkney Mainland, lies Castle farm. Where most farmsteads are erected in dips and furrows for shelter, over 300 years ago, a hilltop farm was built.

The surrounding acreage was abundant with stone seams – a lucrative opportunity thanks to a growing town over the brae. The original farmhouse and shed were built by the landowner to signify the success of his eight quarries. Due to the brass decision to mount the brow of a brae, the farmstead was known colloquially as ‘The House of Folly’, a foil to ‘The House of Wit’ nestled down by the shore. Despite the challenge of ceaseless gales, ‘Folly’ became ‘Castle’ when a second floor was added to the house, making it the firsttwo-storey dwelling in the area.

The farm continued to grow as focus shifted from stone to livestock. New buildings corresponded with a growing inventory of animals, grain, and agricultural machinery.

Generations of farmers of the Castle used the resources at hand; the yield from their own quarries, which improved the deeper they dug, and reclaimed stone from a redundantkiln were used to expand the steading. The farm’s layout was informed by its daily workings. The majority of labour takes place outside, and with such an exposed site, it was essential for the built form to provide a sheltered area from wind of any direction. An enclosed, central square is protected on all sides by the farmhouse, old stables, and byres. Without a formal plan, the farmstead was intuitively expanded by those who know it best.

Townscape

Nestled at the foot of Brinkie’s Brae lies the fishing town of Stromness. The town is recognisable for quaint, irregular piers and matching gables which seem to have emerged from the sea. Protected by the hill from Westerly gales, Stromness expanded at the mercy of the granite slope to which she clings. The dense configuration of closes, courts, and winding lanes navigate their way up the Brae from the harbour until the severity of the slope forces buildings to disperse. George Mackay Brown, a Stromness native, wrote poetry and stories depicting life in his cobbled home. He exalts his town, his prose often sounding like love letters to his cherished harbour.

Give a town a port; a deep, sheltered bay; and fertile land; and its people have jobs. Give these people shops, bakeries, churches, and a good few taverns, and a community flourishes. And as its community grew, so did its infrastructure. Piers and buildings multiplied along the harbourfront in response to a challenging balance between population growth and suitable land . A dense configuration

of outstretched piers and splintering closes reach into the sea and up the brae. The herringbone street pattern meanders from North End to The Point of Ness, pinching tight in places and expanding in others. This fluctuating route creates sunny spots for neighbours to congregate and linger. Three-storey buildings break Northerly gusts while neighbours perch on windowsills, dykes, steps, or knee-high pavements when in lieu of a vacant bench. These nodes within the townscape nurture the kind of chance meetings essential to a small community.

Huddled homes shelter their lodgers as well as each other; their narrow four pane windows look out onto the water across piers, across boats. Buildings on the seaboard side sit gable end to the sea, maximising permeability and access to the harbour. The main street itself is flanked by a cross-stitch of buildings, while homes further up the hill sit parallel to the shore. These elevated homes take advantage of their position with expansive views across Scapa Flow or out to the neighbouring isles of Graemsay and Hoy.

Stromness sits steadfast in her harbour. She was formed by the hands of her townsfolk, and from the rock of her shores. “The Quarries”, a reef of rock at the point of ness, provided stone for local craftsmen to build shelter for their families and neighbours. Townhouses are stamped with a stonemasons’ mark. Homes were roofed using slate from a quarry only three miles away. Dykes were built from the granite of the brae.

Moving Forward

There is a privilege and responsibility that comes with designing our built environment. The pressure is amplified when building in a sensitive landscape steeped in history. A firm grasp of where we build is essential, and architecture should be proposed which is both sensitive to, and respectful of its environment. All aspects of ‘context’ surrounding a proposal must be understood - climatic, economic, physical, social, historic. In recent years, there has been an increased awareness around the sustainability of contemporary architecture with “climate crisis” now a firm part of our lexicon, pressure is applied not least from an architect’s own conscience, but from public opinion as well.

Sustainability in isolation is impossible. There can be a tendency to apply sustainability to architecture instead of designing with intent from the beginning. To achieve environmental sustainability, architecture must set out to be responsive. A reciprocal relationship with its surroundings must be prioritised from the outset.

The community is proud to be enthusiastic about sustainability, especially when it comes to a circular economy. The ability to invest in our own industry and prioritise the use of our own resources has been demonstratively important. Promotions for shopping local, and an interest in moving towards a clean and locally generated energy has grown. Orkney was outraged over the council’s controversial plan to outsource stone for a major development, instead of using local quarries; the community cares enormously about protecting the industries which sustain them. It is the responsibility of those who serve the community to listen.

Notions of “environmental design” and “sustainable architecture” may not have existed when Skara Brae was built, or when 18th century farmers erected their steadings, but responsiveness was intuitive. They were people deeply in tune with their surroundings, and their buildings were sensitive and sensible as a result. Incentivised by a need for shelter and a localised material stock, architecture was tailored to its setting. These principles are entrenched in our rich Orcadian built history, and provide a lasting example of how to build with the land.

The Neolithic settlers of Skara Brae understood the challenging weather conditions of the Northern isles, and the importance of shielding themselves. They burrowed to insulate and protect their homes and circulation network with the mass of the ground. An equal treatment of spaces demonstrated a prioritisation of community, and shared access routes between houses were designed into the fabric of their architecture. Their robust building methods formed an architecture which has endured over 5000 years of gales and coastal erosion.

There are few people who understand the landscape as intimately as farmers. The way they design and build their farms reflect their holistic way of working. Farmsteads are expanded and evolved over hundreds of years by a responsibility to give back to the land to which they tend. Their prioritisation of function makes for an honest architecture designed for efficiency. Sheltered pockets of outdoor space and deliberately nondescript, multi-purpose buildings place functionality at the forefront of design, working with the natural conditions and constraints of their land.

Stromness is an exemplar of a characterful place with an architecture adapted to the unique quality of its natural surroundings. The town has an impressive density which feels appropriate and comfortable. The organic development of the townscape prioritised permeability for pier access and harbour views, not refuse vehicles and right angles. The brae allowed the town to establish an integrated, irregular street pattern and surprise moments, permitting a community to enjoy the fortunate shelter of their harbour.

As we strive to create an environmentally sympathetic architecture, our indigenous built history sets a lasting precedent. Huddled, robust architecture responds to the elements with a honed efficiency, and with community at its core. Although humble in scale and construction, these buildings are symbolic of a much bigger principle – that one can build with and from the land to produce a intuitive and thoughtful architecture.