I knew a Croatian, Tony, who defended Dubrovnik during the Serb and Montenegrins’ Siege of 1991-92, part of the Balkan Wars that split the former Yugoslavia into Balkan pieces. He told me that some of the institutions of the Yugoslav State had survived the early months of the war so that it was live on State TV, during a current affairs programme, that a Serb general announced that they were launching the assault. There were gasps from the audience and people started shouting that Dubrovnik should not be targeted because it had no strategic significance and was full of people, beautiful and old. The General rose up in rage and pounded the table shouting ‘YES WE WILL BOMB IT, WE WILL BOMB IT FLAT! THEN WE WILL REBUILD IT; WE WILL REBUILD IT BETTER; WE WILL REBUILD IT OLDER!’

The General would be well-served by today’s ‘Build Back Older’ brigade: the historicist architectural and urbanist movements advocating a return to traditional values. For in today’s world of shoddy and meretricious building where should we find solace but in the past?

I love old buildings. Sometimes the minutiae of the evolution of their style, or the wars between those styles, I can take or leave; but at other times, like when I read my friend Ian Hamilton Finlay’s poetic axiom of classicism and the humanism that gives life to it, my heart soars.

At others, again, I notice how architecture, in all its styles, including his, gets deployed tyrannically, to fortify power and status. But what I love most about old buildings is the solidity and craft of their vernaculars: simple palettes of natural materials brought together with craft and skill, all governed by a culture of building that understood how materials and climate work together in harmony to assure environmental and fabric sustainability alongside human comfort and cultural expression. And how, augmenting that solidity, these same crafts lift that simple palette into the art of architecture in such ways as Finlay describes – more an act of worship of the art of building than simple decoration.

But I don’t think we should look at the past uncritically: take for example the historic architecture of southern Spain, where Islamic Al-Andalus – graceful, balanced, finely-tuned to nature and the exigencies of a scorching climate – provides humane contrast to the egregious bombast of the Christian Reconquista that supplanted it, with the power, wealth and privilege of Church and Monarchy triumphant. Extreme, kleptomanic wealth, with Palatial frontages and great Churches with cherubim dripping in gold and jewels thrust in the faces of the poor and pious.

This opens up a different way of looking at the past, where, as in Mudejar Spain, that simple palette is deployed to support human comfort and social interaction. And we can bring the same critical view to bear on modernism, contrasting bombast with its great humanising – and often Scandinavian-led – branches that emphasised light, connectivity to nature and democratic gathering space, that all remain in any assessment of the power of good, evidence-based design for supporting our collective wellbeing.

So we should reject this dividing line between traditional and modern and, instead, look for the humane in all building, to what we might call its lifefilledness: how they’ve been warmed by occupation, and how much human interaction they have promoted and how much is to come, as their sturdiness gets adapted to suit changing uses and the changing ways we live.

So we should reject this dividing line between traditional and modern and, instead, look for the humane in all building, to what we might call its lifefilledness: how they’ve been warmed by occupation, and how much human interaction they have promoted and how much is to come, as their sturdiness gets adapted to suit changing uses and the changing ways we live.

It is true, though, that many of these sturdy vernacular building technologies were left behind in the 20th century. However, many modernist buildings – schools, hospitals, housing estates – were largely built with a similar integrity, though their sturdiness has not saved them from a development lobby that requires a river of public money to finance a ruinous cycle of built-in obsolescence as we build for ever-decreasing life cycles of construction, decay, condemnation, and landfill. “Dealflow” our financial masters call it. (I wish the traditionalist lot would expend more of their energy in fighting the destruction of the past, the bizarre inequity, for instance, of charging 20% VAT in Britain, on the repair of historic residential property, and zero-rating demolition and newbuild. Though this is may not be a problem for them when they get to Build Back Older…)

What marks construction of the late 20th and 21st century is the financial pressure to skimp on craft and integrity, substituting new, composite materials, bolt-on tech and shoddiness, often added to correct faults inbuilt by the last innovation, and all whipped-up by industry keen to capture our cash. Most contemporary construction, in whatever style, is formed from a sort of botched, contemporary vernacular that is toxic: insulation foamed with cyanide (that killed the residents of Grenfell, the London social housing tower block that burned and took 72 lives); interiors sealed in poly bags, to trap water vapour, CO2 and toxins inside (so dramatically increasing our respiratory problems) and structural timbers full of arsenic, to try to save their skimpiness and the bad detailing that surrounds it from wet rot (and increasingly present in our atmosphere as the cost-of-living crisis drives people to burn timber taken from builders’ skips).

As a profession we are persuaded to accept this as given and fight over the remnants: the look and style of the shoddy that’s built, presenting it as trad, with its buttons and bows, or modern.

Enter the Building Back Older industry, to argue for a top-quality version of the former: in Britain King Charles-inspired Royalist Urbanism, in the US and internationally Building Beauty, apparently grown out of the work of the late Christopher Alexander but – as I studied and worked with Chris and knew his radicalism well – with stylistic principles diametrically opposed to his radical recovery of place and craft. And in Sweden, and spreading out across Europe from it, the Architectural Uprising.

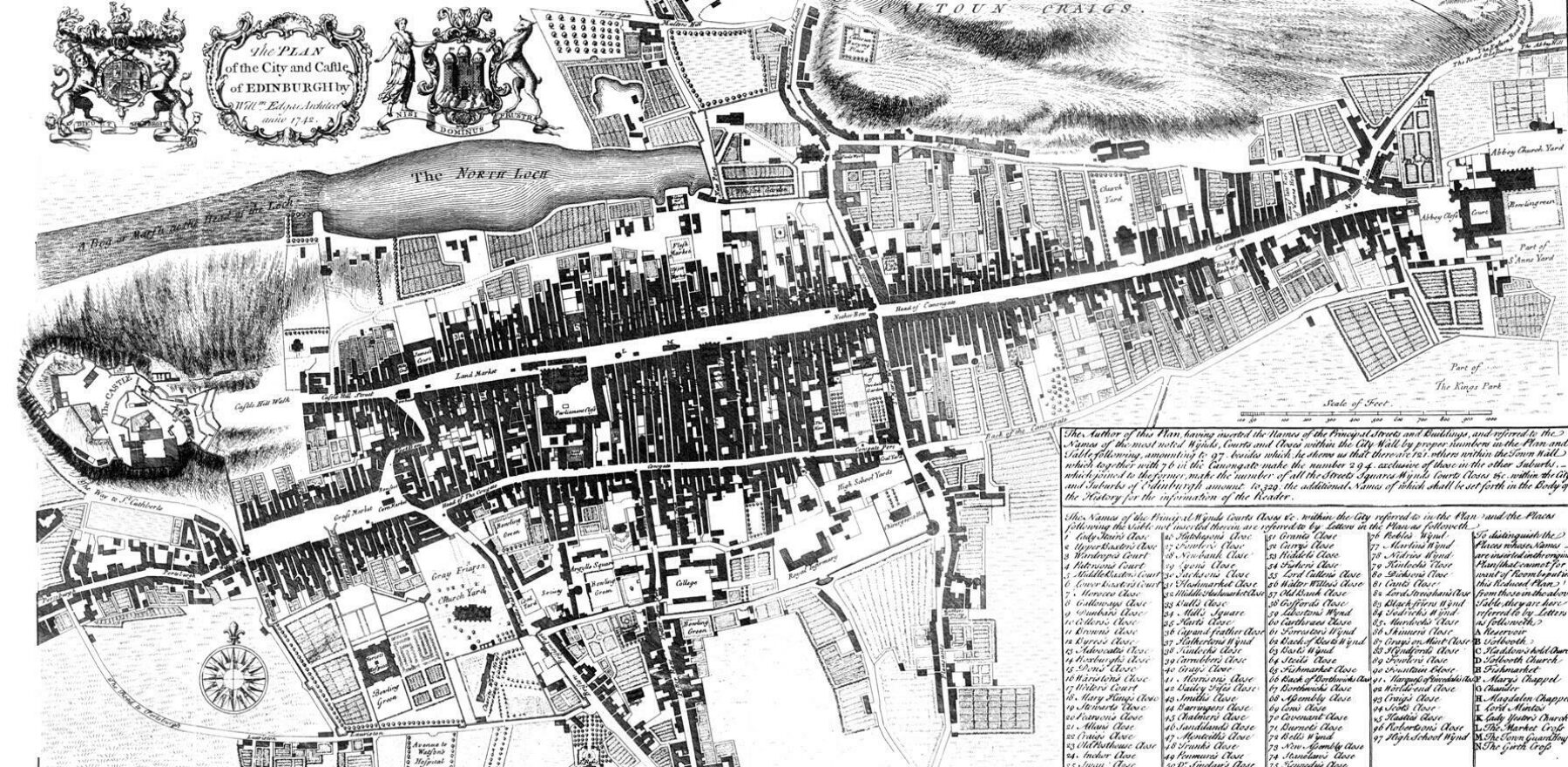

It’s important to understand how narrow and doctrinaire the ‘traditionalists’’ view of tradition is. Traditionalist guru Leon Krier defined ‘The City’ as ‘a conurbation of streets and squares bounded by continuous blocks of buildings punctuated by occasional icons’. But not my City (fig. 4, below), for in their pre-Enlightenment form Scottish cities like Edinburgh had no streets and squares and no continuous blocks, just elongated Mercats, Courts and Closes.

And, similarly, Scotland’s towns and villages (fig. 5, right) turned buildings perpendicular to draw boats up from the sea, shelter from the wind and enclose space for domestic animals.

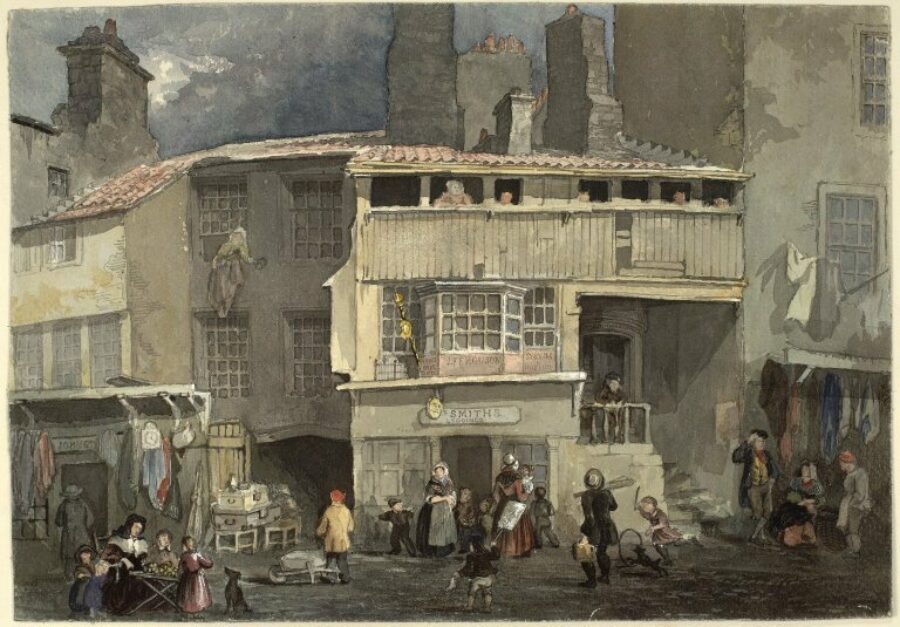

I have seen traditionalist proposals that imposed blootering nineteenth century urban superblocks, ‘built back older’ over the remnants of Edinburgh’s delicate medieval court-and-close plan. And been lectured to by no less an authority than the then-Prince Charles, who assured me that the key to traditional architecture is that it consists of ‘vertically orientated windows in a masonry wall’. Which nonsense he communicated to me in my Edinburgh’s Old Town, where my favourite lost building is the wonderful Symson’s Land which, as its upper stories were timber framed, and as it was built as a printer’s shop, requiring lots of even light, had the lovely horizontal stripped windows so characteristic of mediaeval Scottish architecture – and of modernism, equally receptive to good light.

Such doctrinaire narrowness leads to daftness like a little frame building my practice designed for literature and in tribute, nearby in the Old Town, being described by a celebrity Scottish postmodernist as ‘brutal’.

At its worst traditionalism is a colonialist project of cultural cleansing, wiping out the rich, local urban and architectural traditions of place and nation, and imposing a single, 19th century, European neoclassical orthodoxy upon them.

Architectural Uprising helpfully maintains an ‘Atlas of New Traditional Architecture’ (Built Back Older) to celebrate the progress of this new orthodoxy, and I cycled out to view what will be their newest entry near me, of over 450 new homes in Longniddry Village, in the rich farmland east of Edinburgh, masterplanned – so ‘classically’ laid out – and Design-coded by Royal favourite Ben Pentreath.

What struck me first – and is remarkable, in every new traditionalist, ‘Royalist’ urbanist settlement I’ve seen – is the absolute, obsessive focus on the primacy of the car, hypocritical when you see how their marketing bangs on about people and community, understandable when you think that they are selling to a middle-class suburban demographic.

So the layouts focus on car movement, and then the traditionalists are so OCD-proud of the perfect, smoooth tarmac they roll out that they can’t bear to spoil it with actual parking, and so tidy-up the cars behind the houses, where gardens and playgrounds should be. And therefore, instead of grass, trees, and children we get controlled parking, and garages in a sort of converted-stable-neovernacular, and more tarmac. What’s then remarkable about the streets they’ve emptied is how boring and even threatening they feel: Midwich Cuckoo-like without footfall and the everyday, neighbourly interactions that go with parking.

And there’s a consequent, additional marketing hypocrisy. Whereas they also bang on about traditional materials and traditional detailing it’s hard to notice such niceties past the acres of smooth tarmac. So in my Design Code I’d note: ‘Keep private transport in the streets, where it belongs, and out of the gardens which should be kept for children and planting’.

On the positive! It’s good to see density, and someone actually being prepared to pay design fees for simple buildings and slightly improved materials, that they clearly believe will result in better sale values and a more cohesive community.

But from a seat on the number 44 bus, upstairs at the front, travelling from the centre of my Edinburgh out through its suburbs, you see the ordinary, ill-considered version of Building Back Older. Almost everything out the window pre circa 1919 looks, and feels, good, well-crafted, and solid. Then scattered amongst them are a few 60s and 70s developments with some modernist sensibilities that raise the heart: homes that turn to embrace a view towards the river, articulate to shelter and catch the sun and, in general, have some thought and spark. But the style battle that the Build Back Older brigade trumpet has already been won, for these wee sparks are engulfed and extinguished by contemporary estates of pitched-roof, brick-boxed versions of Longniddry Village, but without the density, design fees, and slightly better materials.

Given all this, the Wrong Question is: how do we accept our current, contemporary suburban layouts and toxic way of building and trick them up to look solid, classic, sustainable, how to get that warm, nostalgic glow? The housebuilding industry has a technical term for these tricks: gob-ons, that is, the pediments, half-timbering and the like that they ‘gob’ onto their basic box as debasement of their craft. So, in the terms of the industry’s concern, what they want to know is what sells, as well as what gets them the thumbs-up from a Planning Committee. Are the gob-ons traditional or contemporary? Are the roads rural-wiggly or Georgian-grid? And, in the light of the climate emergency, whether to pivot to what I was assured was the responsible industry reaction, that they now do Eco-Gob-ons: wee windmills, photovoltaics and the like. (I kid you not – this was a serious Housebuilder industry figure being deadly serious).

In summary, how do we make modern buildings look like old ones? is the wrong question.

So what might be the Right Question? In today’s world of shoddy and meretricious building, where should we find solace in the present?

Speaking personally, and for my practice, what we should be tackling is what a new vernacular might be that suits the way we live now, and the materials to hand and appropriate technologies we have to build with.

The vernacular will always look to materials readily to hand, and societal necessity, then build as simply as possible. So with renewable materials that sequester carbon, in healthy ways that are vapour open but heat-retaining, and without plastic and toxins. So we should use timber, in mass forms, as the structure, with natural insulation outside it (so avoiding the interstitial condensation that then demands poly bags and toxic rot treatments) and, if possible, is exposed internally.

And as to how we set out our communities, we have been lucky enough to have had several small settlements of 35-150 homes to design and lay-out. In all we have our own wee axiom to guide our layouts: to design around people, sunshine and gathering; with groups of homes round courts, closes, or mews, each with living spaces to the south, spilling out into sunny gardens with space to play, dry clothes, and mend a bike, connecting to shared social greenspace – a village green, in effect – where kids can play games and a barbeque can be held.

I like to think that our axioms are grown from the humane, sound principles of modernism that valued light and gathering. But I also delight in noting that they learn from the historic Scottish urban forms that preceded the Age of Improvement, whose ruled rationality supplanted the clachans, fishing touns, and fishbone city urbanism that was so well tuned to Scotland’s climate and sociability.

There is much to learn from the past, but we need to go so much deeper than the colonising traditionalists go. And we need to look much closer at how we live now, and the challenges we face, to produce architecture and urbanism of its time and place.