When I first stood, sodden, within Orkney’s Ring of Brodgar, I thought of the classical Greek view of a world composed of earth, air, fire and water, and how that made no sense here: ringed as the stones were by sea, sea loch, brackish loch, freshwater loch, bog and drowned land, and with air so laden with soft rain you could swim through it, water rules all.

The Ring itself was a pre-Euclidian act of worship to water, the ditch encircling the stones originally dug to such a depth that it would have been filled; the whole henge describing a perfectly-circular, sacred Island-within-the-Island Archipelago.

Water defines Orkney. We read a map of Britain as a plan of a house with its front door facing France and routes branching up across the land. But, for much of our history, the Channel has been a war-front; and, in any case, bogs, forests and brigands made land travel tortuous. Turn the map through 180° and Orkney is the way in to Britain: not so much a front door as the fulcrum of great sea routes, out of Scandinavia and the Baltic, round and down the Minch, through the Irish Sea and out into the Atlantic, then round and into the Mediterranean. This is one of civilisation’s key arteries and Orkney turns out to be not far-flung and at the edge of civilisation but, water-borne, at its centre.

Publication / Architecture Today

Published in the regular “My Kind of Town” series – more a rumination about place than town, and the start of an understanding of how our forebears worshiped the elements – in Orkney, water.

The dizzyingly-rich continuum of built heritage on the Islands proves this: from the 5,700-year-old Knap of Howar farmhouse on the island of Papa Westray (the oldest standing ruin in Northern Europe) through the stone age village of Skara Brae, stone henges like Brodgar, chambered tombs like Maes Howe and the huge Neolithic Temple complex of the Ness of Brodgar, at the Brodgar Fulcrum, newly-uncovered in the last few years; to the extraordinary Iron Age Brochs – huge, open conical towers with inhabited walls – and the Pictish villages that surrounded them and Viking villages and longhouses that supplanted them; the great Norman Cathedral of Kirkwall, built by masons from Durham and the Renaissance Bishops’ Palaces that surround it; the intricate urban form of the herring fishing towns of Stromness and Kirkwall; Lethaby’s Arts and Crafts masterpiece, Melsetter House; and, at Scapa Flow, the twentieth century military remnants, from Italian Nissan Hut Chapel to scuttled German fleet, of what was, between the First and Second World Wars, one of the greatest naval bases in the world.

If Orkney is my context, Stromness is my town. The constant throughout that near 6-thousand year built context, from Skara Brae to Melsetter, is the need for shelter from the North’s weather – for social closening – and the consequent positioning of principal buildings to enclose and shelter secondary space. Stromness was the haven for herring fisheries and last watering place and recruiting ground for explorers like James Cook and traders like the Hudson Bay Company. It provides a very beautiful, particular form of sheltering northern urbanism, where the main street lies parallel to the foreshore and buildings sit perpendicular to it, one gable to the street and one presenting a pier-end to the sea, with intervening constructions perpendicular again, parallel to the street, sheltering closes, courts and gardens. The line of the street and its buildings is deliberately winding, loose and open, the gaps, snecks and closes teasing and dispersing the wind and the whole form beautifully-tuned by work, weather and water.

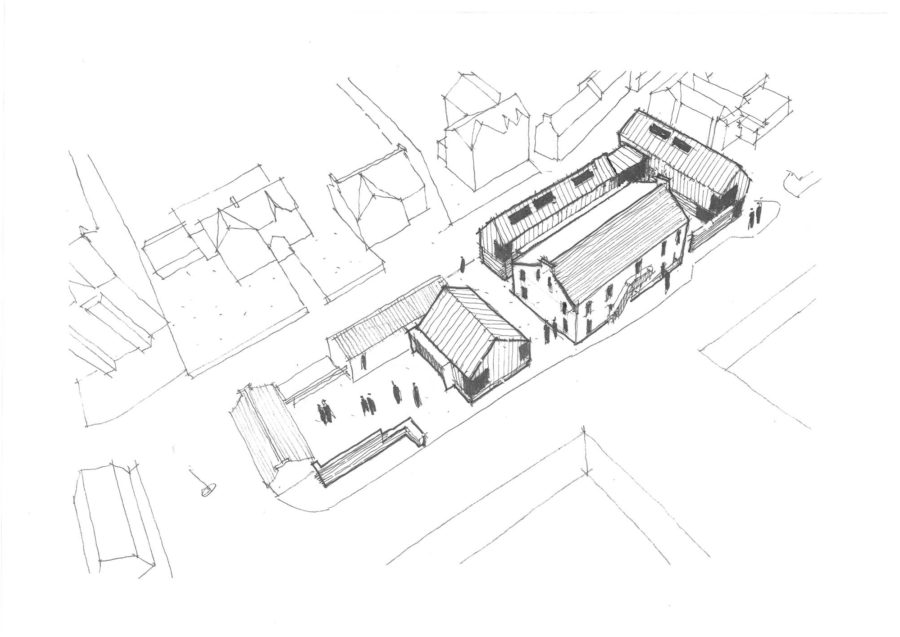

We are onsite in Stromness, near where Reiach and Hall built the lovely Pier Arts Centre, at the Pierhead where the great ferries dock. Our site was the beach where the herring were gutted and it has never had much more than sheds on it, save for the eighteenth century grain warehouse which sits foursquare to the shore, and which we incorporate and build around.

Our brief is for a civic hub, with police, social services, district registrar, a retail building and a Library (with a room dedicated to the poet George Mackay Brown overlooking the street he walked up to the bar he drank in every Stromness day) providing an ideal of civic and cultural regeneration, with all arranged to form the courts, closes and sheltered public spaces that characterise Stromness. We like responding to the particularity of this place: to understanding the strength and contemporary relevance of its traditions. A northern corrective, we hope, to the prevailing beaux arts urbanist view of the past.