Moidart, like much of Scotland’s West Coast, has a heartstopping view out to the west, and as the sun goes down over the Isles and the sky flames we witness the drama of the heavens.

Studded around the Moidart coast on high promontories and rocky islands close to the shore are five “vitrified forts”, circular walled enclosures from the Iron Age and earlier that appear across northern Europe, though Scotland has most of them.

They were created by firing the stone in their walls so it melts and fuses, like a rough, stony glass. To archaeologists they are a mystery, for it has not been possible to reconstruct the conditions where a wall built of stone and timber, then fired, has generated a heat intense enough to melt and fuse its stone.

The craft of their construction must have been of an extraordinary high level: huge volumes of stone and even greater of dry wood, laboriously transported to the sites, woven together in ways we don’t understand and fired and baked we don’t know how. High craft and huge effort… all of which went into creating a defensive wall that was, like glass, brittle: actually weakened by the laborious vitrification process.

So poor forts, though they will have been used for this after. But we need to look elsewhere to understand what these structures might have meant for the people who built them. Considering Place and Culture gives us a gateway to their World, for it is hard not to see a halo of flame and smoke from the burning as a primary purpose and a sacred rite, with the drama of fire, water, mountain, island and heaven playing out before sea lochs ringed with Iron Age tribes.

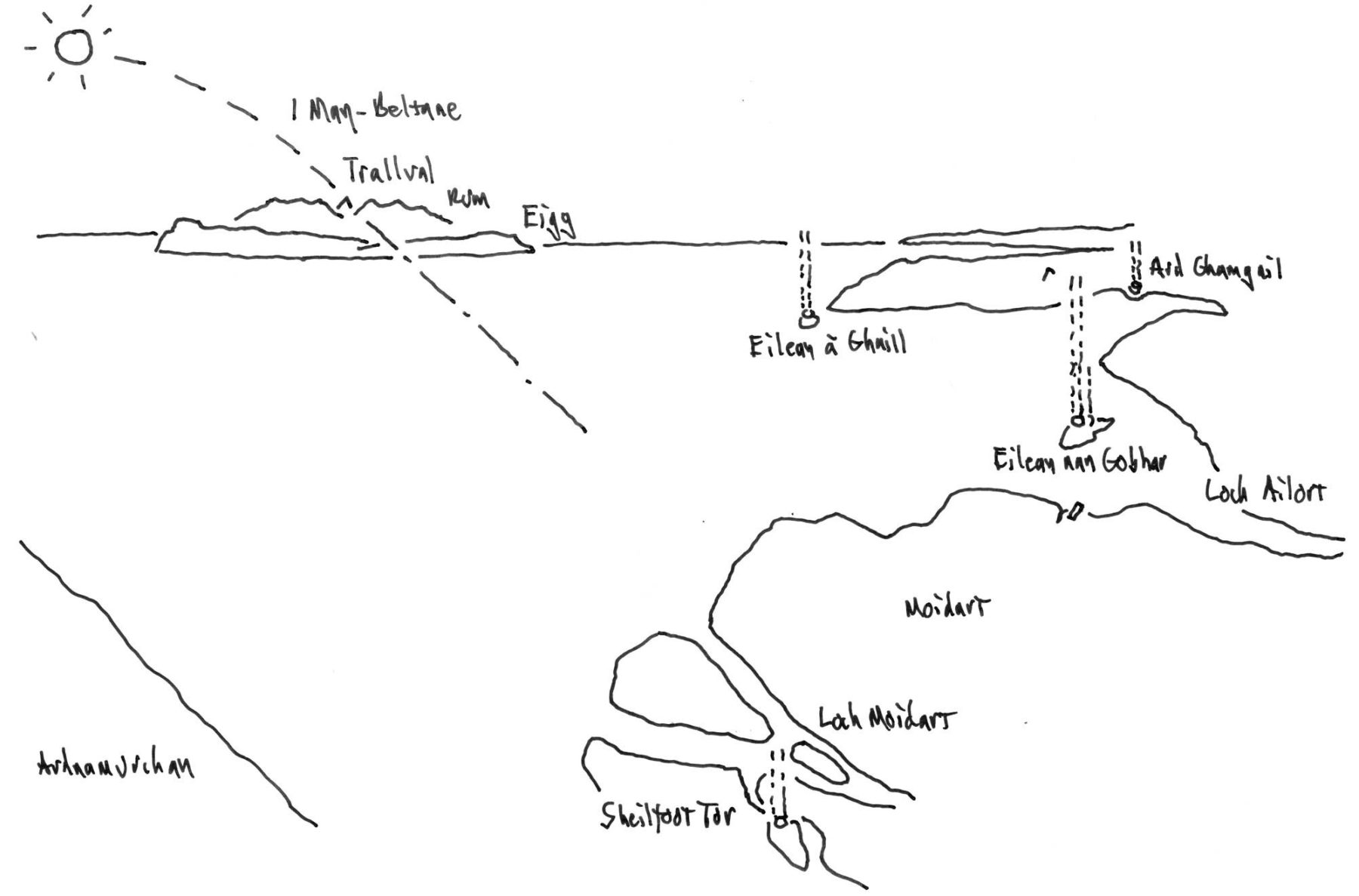

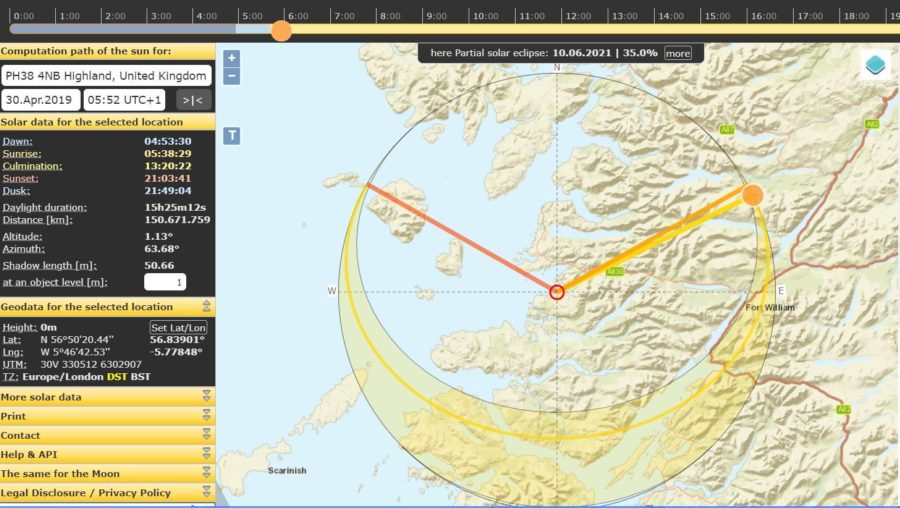

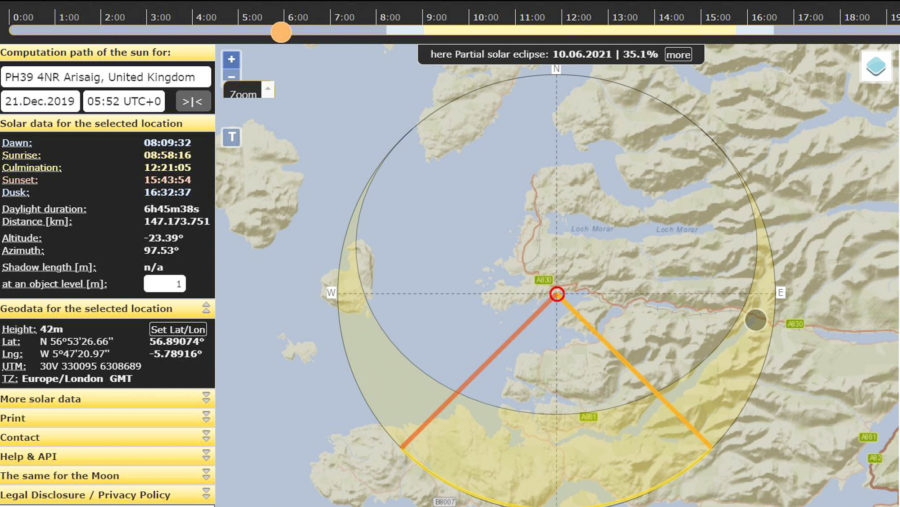

For these structures sit in extraordinary relation to their landscape. Out from Lochs Ailort and Moidart, past the islands to the horizon beyond, springs a big axis. It crosses the low, concave horizon of the island of Eigg, then across the Sound of Rum and through the deep cleft between the great mountain ridges of the Rum Cullin, before disappearing west over the lonely, conical Cullin called Trallval – hill of the Trolls, in Norse. Around the first of May - so around Beltane, the Celtic Fire Festival and one of the primary days of their year – the sun sets into the cone, the whole like some great, celestial conception ritual, as a huge, landscape version of their own predecessors’ caves, chambered cairns and great stone circles.

Publication / Moidart History Group

Further West from Rum is the setting-sun and Tir na n’Og – the Land of the Young, the Celtic Valhalla, which lay in the west and where heroes went to rest before one day returning to their people, in their hours of need. Light, weather, time and space play with these distances when the sun sets directly behind Trallval. How much more must the sinking of the sun across islands and sea have meant, back then, with fire and smoke haloing into the skies?

And there’s an echo of this much later, when the clan chieftains advised Bonnie Prince Charlie to land in Moidart, to launch the cataclysmic Jacobite Rebellion that nearly brought down the British state. Loch Moidart is shallow: hard to navigate and land. But the Tir na n’Og of this sacred landscape would have been the correct place for a hero-king, from beyond the water – from Tir na n’Og – to return from, to his people.

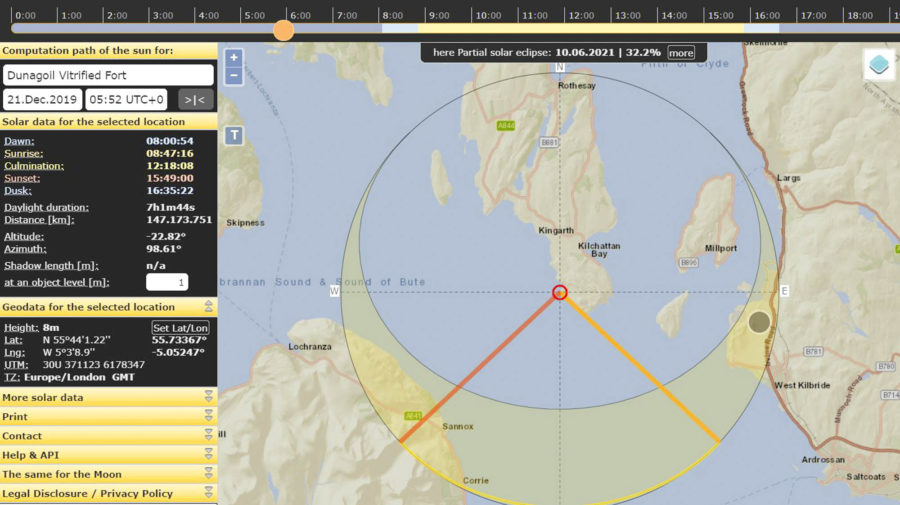

A brief consideration of vitrified forts elsewhere in Scotland reveals other possible Beltane alignments with conical peaks – though it has to be admitted that Scotland abounds in conical markers. Other alignments occur: the fort at Dunagoil, on the Isle of Bute, has a lovely view out to Arran that is an uncanny twin to that of Rum from Moidart, with the symmetrical ridges and deep cleft framing Cìr Mhòr as its Trallval; except that the alignment is not Beltane but for sunset at the winter solstice; the rite, therefore, being of rebirth and renewal - a common pre-historic alignment in Scotland, seen at Orkney's Maes Howe and elsewhere.

And at Moidart the vitrified oddity is Ard Ghamhgail, with its axis to Trallval blocked by the headland; and while there is a wee Beltane cone on that headland there’s also a winter solstice axis, out to the great, decayed, volcanic peaks of Ardnamurchan. Ard Ghanhgail’s human-burnt, vitrified circle, faces the blazing solstice sun setting into this ancient volcano, and itself sits on a candy-striped igneous rock extrusion, vitrified inside the earth.

These are sacred landscapes. The world was made from rock and fire, and our forebears, in marking the rhythms of sun and season that governed their lives, grasped key truths about the origins and energy of life, and worshiped them.

Beltane 2024

It’s tempting, when you witness the sun descending into the cone, to imagine the Iron Age tribes who fired those vitrifications conjuring a Pagan God from it, leaping across the water, down the light, onshore. But that might be to underestimate them, condemning them to the same anthropomorphising tendencies that blight many of the world’s “Great” religions. The deliberate melting of rock, circled round atop candy-striped, molten, igneous rock, all set in alignment with the molten sun firing the decayed volcano, might be a deliberate and composed act of homage to the landscape itself.